In Korea, an unorthodox form of stress relief has become a growing phenomenon: voluntary imprisonment. People from all walks of life, from students to office workers, are choosing to take part in this unique practice as a coping mechanism for their anxiety and depression.

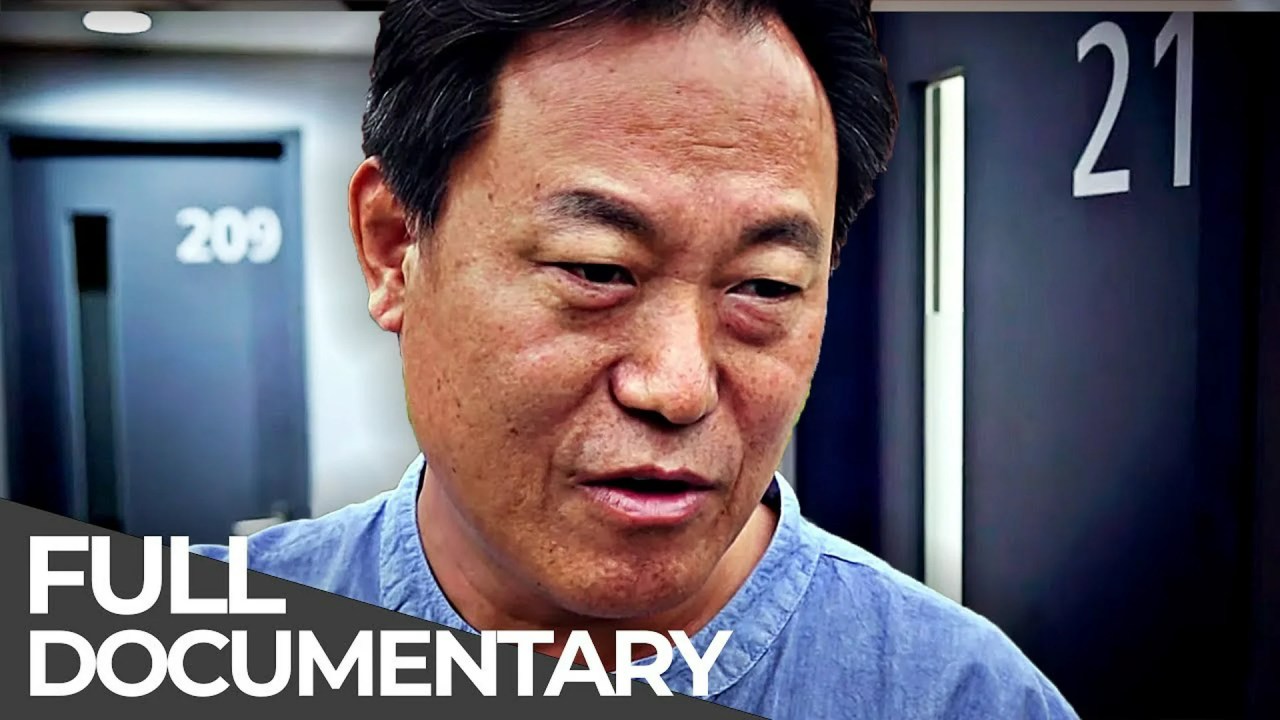

The concept of voluntary prison time was popularized by a documentary released in 2019 called “Prison Time”. It follows the story of one man who voluntarily entered a Korean prison for three months. He says he does it for two reasons: to recharge his mental batteries and to understand what it’s like to be incarcerated.

The film garnered both national and international attention, prompting many viewers to ask themselves: Could voluntarily going to prison actually be beneficial? The answer is yes—for some people at least. One professor who watched the documentary said that “voluntary imprisonment can provide an escape from the everyday pressures of life and help individuals find new perspectives on their lives”.

This notion of voluntary confinement has a long history in Korea, stretching back centuries when monks would voluntarily enter into meditation retreats as part of their spiritual journey. Even today, in North Korea it is not uncommon for citizens to use prison time as a reprieve from the external pressures they face outside its walls.